| Vidhana Soudha | |

|---|---|

ವಿಧಾನ ಸೌಧ | |

Vidhana Soudha as seen from Dr. B. R. Ambedkar Road | |

| General information | |

| Type | Legislative building |

| Architectural style | Neo-Dravidian |

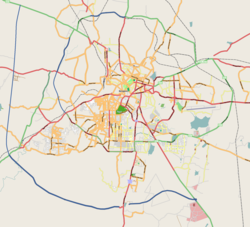

| Location | Ambedkar Veedhi, Sampangi Rama Nagara, Bengaluru, Karnataka 560001 |

| Country | India |

| Coordinates | 12°58′47″N 77°35′26″E / 12.9796°N 77.5906°E |

| Construction started | 1951 |

| Completed | 1956 |

| Inaugurated | 1956 |

| Cost | ₹1.8 crore (US$210,000) |

| Owner | Government of Karnataka |

| Height | 46 m (150 ft) |

| Dimensions | |

| Diameter | 61 metres (200 ft) wide and the central dome, 18 metres (60 ft) in diameter |

| Technical details | |

| Floor count | 4 + 1 basement |

| Floor area | 51,144 m2 (550,505 sq ft)> |

| Design and construction | |

| Architect(s) | B.R. Manickam (Chief Architect) Kengal Hanumanthaiah (Visionary and Project Overseer) |

| Main contractor | KPWD |

| Other information | |

| Public transit access | |

Vidhana Soudha (also spelled *Vidhāna Saudha*, lit. "Legislative House") is the seat of the Karnataka Legislature in Bengaluru, India. Completed in 1956, it houses the bicameral legislature comprising the Karnataka Legislative Assembly and the Karnataka Legislative Council. Regarded as one of the most prominent examples of post-independence civic architecture in India, it stands as a landmark of Karnataka’s political identity, architectural ambition, and cultural heritage.[1]

Designed in the neo-Dravidian style, Vidhana Soudha consciously rejected colonial architectural influences, incorporating elements from classical temple traditions of the Chalukya, Hoysala, and Vijayanagara dynasties.[1] Conceived by Chief Minister Kengal Hanumanthaiah as a “Shilpa Kala Kavya” (sculptural epic in stone), its massive granite structure features a central dome, ceremonial staircases, carved pillars, and ornamental woodwork. Inscriptions like “Government Work is God’s Work” and motifs such as the Ashoka Chakra convey ideals of ethical governance and national unity.[2][3]

Beyond its administrative function, Vidhana Soudha serves as a significant civic and cultural symbol. Its premises feature landscaped gardens and have hosted notable events, including the 1986 SAARC Summit. The building has also been featured in philatelic commemorations and has recently expanded its public engagement through permanent LED lighting installations and guided tours initiated in 2025.[4][5][6][7][8][9] Its iconic design has inspired similar government buildings across Karnataka, such as the Vikasa Soudha and the Suvarna Vidhana Soudha in Belagavi, cementing its status as a powerful emblem of the state's governance and cultural pride.[10]

History

[edit]

The two houses of the legislature of the Kingdom of Mysore, the legislative assembly and the legislative council, were established in 1881 and 1907 respectively. Sessions were initially held in Mysore, with joint sessions taking place at the Bangalore Town Hall. After the independence of India in 1947, Mysore acceded to the Indian Union, and the capital of Mysore State was shifted to Bangalore. The legislature temporarily moved into the Attara Kacheri, a British-era structure that also housed the High Court.

To accommodate the expanding administrative needs of the state, a new legislature building was planned. The foundation stone for the Vidhana Soudha was laid by Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru on 13 July 1951, under the administration of Chief Minister K. C. Reddy. The original proposal envisioned a two-storeyed brick building with a floor area of 174,000 square feet and an estimated cost of ₹35 lakh (US$41,000).[2] However, contemporary critiques later described such estimates as outdated and incomplete, with essential items omitted and no serious attempt to revise costs or designs prior to execution.[2]

Following the 1952 elections, newly elected Chief Minister Kengal Hanumanthaiah undertook a bold revision of the project. The new plan, sanctioned on 23 April 1952, envisioned a monumental granite structure over 500,000 square feet in size, intended not merely as an administrative headquarters but as a symbol of Indian democracy and civilizational pride.[11] Hanumanthaiah defended the cost escalation by noting that the revised structure offered nearly three times the area, constructed with superior materials, making it more economical per square foot than the earlier proposal.[2]

According to his biographer, the redesign was partly inspired by a remark from visiting Russian dignitaries who found the Attara Kacheri unimpressive. Determined to create a more fitting symbol of India's democratic future, Hanumanthaiah resolved to build a "Shilpa Kala Kavya"—a sculptural epic in stone.[1] His background as a fighter for independence and his strong belief in maintaining Indian and particularly Kannadiga traditions and culture were key influences on the building's design.[3] He reportedly saw the construction of the Vidhana Soudha as a "shilpa yagna"—a sacred offering in stone—elevating governance to an ethical and spiritual act.

The project soon became a subject of legislative scrutiny. A committee was formed to investigate alleged cost overruns, but its work was hampered by ambiguities: it had originally been constituted to oversee irrigation projects, not public building audits—a fact clarified in the Assembly by legislator Sir L. Siddappa.[2] Some legislators questioned the committee's conduct, with one critic stating that its members had "behaved more like overlords than impartial judges."[2] Meanwhile, the State Accounts Department admitted difficulties in financial monitoring, with an official stating that "accounts are in an unsatisfactory condition" and requesting more staff.[2]

Amidst these debates, Hanumanthaiah defended the vision behind the project. In a legislative session, he humorously remarked that he was "already being accused of overspending money" and hoped not to be accused of "overspending time" on his speech. The Speaker replied, “Let him finish his speech today… he may take five or ten minutes this way or that, it does not matter.”[2] Hanumanthaiah famously articulated his vision in response to a Russian cultural delegation that queried if India had its own architecture, stating his desire for a building that reflected India's heritage rather than European styles.[3]

Despite political controversy, construction proceeded rapidly. Vidhana Soudha was completed in five years and formally inaugurated on 28 September 1956. As the structure rose, it became a site of civic interest. Citizens from across Bangalore visited to observe the granite carvings and the construction of the massive dome. The soil excavated during construction was in such high demand that it was sold to the public, reportedly fetching ₹1 lakh.[2] The choice of granite for the building also made economic sense given the lack of steel and glass at the time.[3] Masons skilled in the Dravidian tradition had to be recruited from places like Karaikudi and Tiruchirapalli in South India, working for extremely low wages.[3]

Construction

[edit]The foundation stone was originally laid by Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru on 13 July 1951 at a site proposed by the then Chief Minister K. C. Reddy. However, after taking office in 1952, Chief Minister Kengal Hanumanthaiah rejected the initial location and selected a new site—a sloping tract of land directly opposite the colonial-era Attara Kacheri. The change was both strategic and symbolic: the elevated position allowed the new building to visually dominate the surroundings and to face the High Court, representing the assertion of democratic authority in postcolonial India. The original foundation stone, located within Cubbon Park near the Press Club, was not moved and remains at its original location.[12]

Estimates of construction costs for the original two-storeyed structure stood at ₹33 lakh (US$39,000), with the final cost of the redesigned granite building reaching ₹1.8 crore (US$210,000).[11][13]

Over 5,000 workers were employed during the construction process, including more than 1,500 sculptors and artisans, many of whom were brought in from the Shimoga–Soraba region, known for its heritage in stone carving.[2] The technical execution was overseen by a team of 300 junior engineers and 9 senior engineers, under the leadership of chief architect B. R. Manickam, who was a civil engineer and town planner. He was assisted by Hanumanthiah, a young architect trained at London's Architectural Association (not to be confused with Chief Minister Kengal Hanumanthaiah).[14] The planning phase involved the preparation of over 1,000 architectural and engineering drawings, underscoring the complexity and ambition of the project.[2]

Construction was completed in 1956, culminating in a structure that was both monumental in scale and deeply rooted in traditional symbolism.[15]

Although widely praised, the project attracted criticism for its substantial escalation in costs. In response to public and political concerns, the state government appointed a committee to investigate the expenditure. The inquiry found no evidence of personal misconduct or financial impropriety, attributing the increase to the expanded scope, design enhancements, and the monumental scale of the work.[1] The escalation was also consistent with trends in other major public works of the period, many of which faced similar revisions due to inflation in labor and material costs.[2]

For landscaping and engineering guidance, Hanumanthaiah consulted eminent figures such as M. Visvesvaraya and Gustav Krumbiegel.[1] Contrary to popular belief, no dedicated technical advisory committee was constituted for the project; oversight and execution remained solely with the PWD.[2] Hanumanthaiah is reported to have personally monitored expenses and reviewed bills, a point often cited during debates defending the integrity of the project.[2]

No private contractors were engaged. The PWD executed all phases of the construction, maintaining tight administrative control over quality and finances. Prisoners from the Bangalore Central Jail were also deployed for certain construction tasks, working alongside artisans and engineers.[1]

The soil excavated during foundation work was used to level a depression in front of the Government Arts and Science College, creating a new public playground. The remaining soil was sold to the public and reportedly fetched ₹1 lakh, reflecting the level of civic interest the project generated.[2]

Despite the enlarged scale, Hanumanthaiah later affirmed that the core vision of the original architectural plan was retained, stating that "even today, the building has all the appearances of the original plan."[2]

Among the international dignitaries who visited the site during its construction were Queen Elizabeth II, Yugoslav president Marshal Tito, the Shah and Queen of Iran, Soviet Premier Nikita Khrushchev, and United Nations Secretary-General Dag Hammarskjöld. Hammarskjöld reportedly remarked that such a monumental structure could only be built by a people with vision and pride in their freedom, highlighting the symbolic importance of the Vidhana Soudha in postcolonial India.[1]

Architecture

[edit]The building was constructed from grey granite sourced from areas around Hesaraghatta and Arahalli. Greenish-blue granite from Mallasandra was used for lining the interior quadrangle. Magadi pink granite and Turuvekere black granite were employed for decorative purposes.[2][16]

It was designed in the neo-Dravidian architectural style, incorporating elements from various dynasties such as the Chalukyas, Hoysalas, and Vijayanagara. The design was intentionally based on traditional Indian architectural principles and rejected colonial Gothic and Indo-Saracenic influences. Architectural inspiration was drawn from Karnataka’s historic temples, especially those found at Aihole, Pattadakal, and Belur.[1]

Unlike the earlier plan for a modest brick structure, the final design employed granite throughout, lending the building a sense of permanence and monumental solidity.[2] The scale and ornamentation of the building—including expansive foyers, massive staircases, and a prominently sculpted dome—were envisioned by Hanumanthaiah as components of a "Shilpa Kala Kavya" (sculptural epic in stone), blending functional architecture with cultural expression. The central dome, visible from afar, was designed to crown the skyline of the city and reflect the dignity of the democratic state.[2] The interior architecture includes broad foyers, generous staircases, and spacious waiting areas, designed to welcome both legislators and citizens alike.[2]

Hanumanthaiah viewed colonial-era styles such as Indo-Saracenic and Gothic as remnants of imperial domination, and sought to replace them with an architectural language rooted in Indian civilizational aesthetics. He envisioned the building as a civic text—an embodiment of democratic ideals—where monumental scale, indigenous symbolism, and carved inscriptions would inspire values such as the sanctity of governance and dignity of labor. The proportions of the structure drew on principles from traditional temple architecture and vastu shastra, yet were executed using modern construction methods.[2] The granite used was sourced entirely from Karnataka, making the project an assertion of regional identity and economic self-reliance.[2] The absence of a formal architectural committee allowed for a direct translation of Hanumanthaiah’s vision into built form, unimpeded by colonial or bureaucratic filters.[2]

Symbolic elements incorporated into the design include domes modeled on temple shikharas, ornately carved granite pillars, chariot wheels, and motifs echoing the Ashoka Chakra. These elements were chosen to represent the continuity of Indian civilizational values and the dignity of democratic governance.[1]

As construction progressed, the site became a popular attraction for citizens. Crowds gathered regularly to witness the rising granite structure, admire the sculptural detailing, and track the progress of the monumental dome. School groups and tourists frequented the area, and press reports from the time often highlighted the public's sense of ownership and fascination with the project.[2]

Architectural influences

[edit]The architectural features of Vidhana Soudha were drawn from a synthesis of classical Indian and global influences, selected deliberately to represent cultural pride, political independence, and modern statehood. The central dome, which crowns the building, was inspired by the Brihadeeswara Temple at Thanjavur and also evokes the dome of the Capitol Building in Washington, D.C., symbolizing the fusion of Indian heritage and democratic ideals.[2]

The broad eastern steps are reminiscent of the approach to the Viceroy’s House in New Delhi (now Rashtrapati Bhavan), but repurposed here to convey the authority of a democratically elected government. The stone latticework (jalis) and arches incorporate elements of Rajasthani and Indo-Islamic design, while the jharokha-style balconies draw from the Red Fort, visually reinforcing the connection to India's imperial past—but with the people, not kings, at the center of power.[2]

The carved friezes and interior motifs take inspiration from the Ajanta Caves, reflecting an artistic lineage that emphasizes spiritual beauty, harmony, and permanence. These design choices were not ornamental alone; they were intended as a form of cultural pedagogy—an architectural narrative of India’s civilizational continuity and postcolonial sovereignty.[2]

The building’s elevation above the colonial-era Attara Kacheri, axial symmetry, and layered spatial access mirror traditional Indian temple architecture. This staging of space transforms the building into a civic temple, where the rituals of democracy replace religious rites but retain sacred overtones.[2]

Hanumanthaiah described the building as a "Shilpa Kala Kavya"—a sculptural epic in stone. Through this idiom, he aimed to counter colonial architectural legacies by creating a monument that would embody the philosophical and ethical foundations of Indian democracy.[2]

Design and construction team

[edit]The architectural planning and execution of Vidhana Soudha was led by chief architect B. R. Manickam, under the overall vision and political leadership of Chief Minister Kengal Hanumanthaiah. He was supported by a team of nine senior engineers and over 300 junior engineers.

Chief Minister Hanumanthaiah took a direct and active role in the design process—reviewing architectural sketches, approving structural and ornamental elements, and overseeing the selection of Kannada inscriptions. His hands-on leadership ensured that the cultural and artistic vision of the project was preserved throughout.[2]

More than 1,500 sculptors and artisans were employed, many from the Shimoga–Soraba region of Karnataka, known for its heritage of skilled stone carving. Their craftsmanship contributed to the ornate granite pillars, decorative friezes, and symbolic motifs that adorn the building.[1]

Over a thousand detailed architectural and engineering drawings were prepared, covering not only the building’s structural framework but also ornamental features, motif alignments, and carved profiles. A dedicated drafting team worked full-time for nearly two years to maintain precision and momentum.[2]

A conscious decision was made to avoid private contractors. The entire project was executed by the Public Works Department, allowing the state to retain close control over quality, costs, and timelines.[2]

In addition to executing the vision, the Vidhana Soudha construction site served as a learning environment. Young engineers and artisans received practical training in combining classical Indian design with modern engineering—an experience that would influence subsequent civic projects in Karnataka and beyond.[2]

Interior architecture

[edit]The interior of the Vidhana Soudha was designed to reflect dignity and grandeur while showcasing Indian cultural values. In addition to legislative chambers, the building houses a central library, archival offices, and a banquet hall for official events. These facilities were part of the expanded design vision introduced by Chief Minister Kengal Hanumanthaiah.

The internal layout echoed the ritual logic of temple architecture, with the legislative chambers occupying a sanctum-like central space and the corridors and foyers resembling circumambulatory paths, symbolizing transparency and accessibility in governance.[2]

Polished granite was used extensively inside the building—not only for structural elements like columns but also for flooring—conveying both durability and solemnity appropriate for a legislative temple.[2] Acoustics in the Assembly and Council chambers were fine-tuned using traditional proportional design principles, while natural light entered through clerestory windows and courtyards, creating an ambient yet dignified interior.[2]

Interior decor elements include polished teakwood furnishings, carved wooden panels, and ornamental lighting fixtures. Traditional Indian motifs such as elephants, lotuses, and temple-style friezes are integrated into the design, symbolizing wisdom, purity, and cultural continuity. Some ceremonial rooms were decorated with carved sandalwood panels, while furnishings were locally designed in collaboration with the Karnataka School of Art, showcasing indigenous craftsmanship.[2]

The building also included designated galleries and waiting halls for the public, reflecting the intent to make legislative proceedings accessible and visible to citizens—a vision of democracy that extended beyond administration to civic participation.[2]

Woodwork and craftsmanship

[edit]High-quality native woods were used extensively throughout Vidhana Soudha to reflect Karnataka’s rich artisanal traditions. The main entrance doors were made of intricately carved teakwood, selected for its strength, longevity, and regal appearance. For ceremonial and high-function rooms such as the Speaker’s chamber, doors were crafted from fragrant sandalwood, a wood historically associated with sanctity and honor in South Indian culture.

Artisans from Karnataka’s temple carpentry traditions were employed to execute the woodwork. Their craftsmanship is evident in the finely etched motifs that adorn these doors, including lotuses (symbolizing purity), elephants (representing wisdom and power), and creepers and floral scrolls that echo temple friezes. These carvings were not merely decorative but were intended to imbue the legislative space with values drawn from classical Indian aesthetics.

The warmth of the wood was intentionally contrasted against the monumentality of the granite interiors, softening the visual tone and creating a more human-scaled spatial experience.[2] Exposed wooden beams and coffered ceiling panels were introduced in ceremonial halls, carved with floral scrolls, creepers, and mandala-like geometric patterns drawn from temple and manuscript traditions.[2]

Alongside teak and sandalwood, regional varieties such as rosewood, jackwood, and softwoods were employed in specific areas, balancing durability with cultural familiarity and local availability.[2]

The site served as a training ground for a new generation of woodworkers who learned to adapt temple carpentry techniques for secular civic architecture, continuing and evolving Karnataka’s artisanal heritage.[2]

Cultural significance

[edit]Vidhana Soudha is regarded as more than just the seat of the state legislature—it is seen as a powerful cultural symbol of Karnataka and post-independence India. Conceived by Kengal Hanumanthaiah not only as an administrative building but also as a national monument, it embodies the ideals of Indian democracy, self-reliance, and civilizational pride.[1]

Hanumanthaiah saw the construction as a "shilpa yagna"—a sacred offering in stone—transforming the building into a secular temple of democracy, where governance itself was elevated to an ethical and spiritual act.[2] He believed that architecture could communicate values, and that the Vidhana Soudha should serve as a moral and cultural landmark for future generations.

The building’s use of local materials, temple-inspired forms, and symbolic carvings echoed Gandhian ideals of truth, labor, and humility. These values were inscribed directly onto the building, with phrases such as "Truth is God" and "Labour is God" appearing at various entrances.[2]

The inscription on its entablature—Government Work is God's Work (Kannada: "ಸರ್ಕಾರದ ಕೆಲಸ ದೇವರ ಕೆಲಸ")—was intended not merely as a motto but as a national civic ethic. It marked a shift from colonial modes of authority to one rooted in ethical public service and participatory democracy.[2]

During its construction, citizens from across Bengaluru frequently visited the site to watch the artisans at work and the dome rising into the skyline. For many, the structure became a source of shared pride and emotional connection, eventually earning the affectionate moniker "namma soudha" (our Soudha).[2]

The building is often described as the "soul of Bengaluru" and has been invoked in literature, art, and political discourse as a metaphor for governance, authority, and the cultural aspirations of a newly independent nation. The use of traditional Indian architectural motifs, native materials, and regional craftsmanship were deliberate choices aimed at reinforcing these symbolic meanings.[1]

Post-construction updates

[edit]In the decades following its inauguration, Vidhana Soudha has undergone several restoration and modernization efforts to preserve its architectural integrity and enhance its public presence. In 2014, the Karnataka Public Works Department initiated a ₹20 crore restoration project to address plumbing issues, roof leaks, and structural cracks, alongside cleaning and repairing the granite exterior.[17]

On 6 April 2025, a permanent LED-based illumination system was inaugurated by Chief Minister Siddaramaiah, transforming the building’s night-time presence. The lighting, designed to operate on weekends and public holidays, enhances the visibility of architectural details and reinforces the building’s role as a civic and cultural landmark.[18][19]

Though widely celebrated as a heritage structure, Vidhana Soudha has not yet been officially designated as such, due to the 100-year threshold commonly applied to heritage classification. However, public discourse and scholarly commentary continue to affirm its importance as a post-independence architectural icon.[20]

Cultural depictions

[edit]Philately and commemorations

[edit]

The Vidhana Soudha has been featured in several philatelic commemorations over the decades, highlighting its iconic status in Karnataka and Indian democracy.

On 15 January 1979, India Post introduced a permanent pictorial cancellation (PPC) at the Bangalore GPO featuring a line drawing of the Vidhana Soudha.[5][21] This cancellation remains in use and is popular among philatelists for its distinctive representation of the structure.

Earlier, in 1962, a commemorative cover featuring the Vidhana Soudha was issued during the First Philatelic Exhibition organized by the Indo-American Association in Bangalore. It included a pictorial cancellation and is now considered a rare item among collectors.[22]

As part of the Diamond Jubilee celebrations of the building, India Post released a special postal cover in Bengaluru on 25 October 2017, bearing the code KTK/79/2017.[6] The commemorative event included a joint session of the Karnataka Legislature, where President Ram Nath Kovind described the Soudha as "a monument to the history of public service in Karnataka," and urged legislators to view the occasion not just as a celebration of the past but as a commitment to the future.

More recently, on 21 January 2025, India Post released a special cover honoring the Suvarna Vidhana Soudha in Belagavi. Though focused on the newer building, the commemorative issue was part of the broader philatelic tradition of celebrating Karnataka’s legislative architecture.[23]

Internationally, the Vidhana Soudha was also featured in a 1997 commemorative stamp sheet issued by Venezuela to mark the 50th anniversary of India's independence. The sheet, which prominently honors Mahatma Gandhi, includes images of key Indian leaders such as Jawaharlal Nehru, Sardar Patel, and Rabindranath Tagore, along with symbols of India's cultural and technological achievements. In the background of one of the stamps, a side view of Vidhana Soudha appears behind the portrait of Gandhi—recognizing the building as a symbol of India's democratic progress and statecraft.[24]

Expanded Public Perception and Cultural Impact

[edit]Lift Man (2017)

[edit]Lift Man is a Kannada-language film directed by Kaaranji Shreedhar, inspired by the real-life story of Kaverappa, a lift operator who served at Vidhana Soudha for 20 years. The film portrays the protagonist's experiences within the corridors of power, highlighting his interactions with various political figures and the personal challenges he faces. Veteran actor Sunder Raj plays the lead role, marking his 200th film appearance. The narrative offers a unique perspective on the daily life and inner workings of one of Karnataka's most iconic buildings.[25][26]

Photo (2023)

[edit]Photo, directed by Utsav Gonwar, is a poignant Kannada film that centers around a young boy named Durgya, whose dream is to have his photograph taken in front of Vidhana Soudha. Set against the backdrop of the COVID-19 lockdown, the film explores themes of aspiration, displacement, and the human cost of policy decisions. Durgya's journey to Bengaluru and his longing to capture a moment at the state's legislative building serve as a metaphor for the broader struggles faced by migrant workers during the pandemic.[27][28]

Comparison of maintenance with similar structures

[edit]The enduring resilience of the original Vidhana Soudha is often highlighted in contrast to the significant maintenance challenges faced by its modern counterpart, the Suvarna Vidhana Soudha in Belagavi. The latter has experienced chronic problems such as rainwater seepage that damaged important documents, moss-covered exteriors, and persistent leaks. These issues have raised concerns about construction quality, despite claims that the same type of stone used in the Bengaluru Vidhana Soudha was employed in its construction.[29]

Activists have demanded a third-party investigation into the Suvarna Vidhana Soudha’s construction quality and have called for criminal action against those responsible for the damage and loss of key documents. This contrast implicitly highlights either the superior construction standards or more effective long-term maintenance practices associated with the older Vidhana Soudha.[29]

Precinct and grounds

[edit]Horticulture and tree cover

[edit]

The premises of Vidhana Soudha include landscaped gardens extending to the double road in front and bordered by rows of trees. Chief Minister Hanumanthaiah consulted Gustav Hermann Krumbiegel, a German horticulturist, for landscape planning.[30]

Tabebuia species—Tabebuia avellanedae, Tabebuia rosea, and Tabebuia argentea—flower in November–December and February–March, producing trumpet-shaped blossoms along avenues and lawns. The Karnataka Horticulture Department cultivates these trees in its nurseries for planting around Vidhana Soudha, Cubbon Park, and other precincts.[31][32][33] One such tree, located at the southeast corner of the Vidhana Soudha, has been described by author T. P. Issar as "probably the most photographed Tabebuia in town," with photographers "waiting for months to catch its two-week glory."[4]

Other species found nearby include Milletia ovalifolia, Albizia lebbeck, Bauhinia variegata, Bombax malabaricum, Jacaranda mimosaefolia, Michelia champaca, Plumeria spp., Polyalthia longifolia, and Samanea saman. These, along with lawns, hedges, and seasonal flowerbeds (marigolds, petunias, impatiens), provide greenery throughout the year.[31]

Maintenance is carried out by the Karnataka State Horticulture Department, which handles pruning, soil aeration, and replacement of seasonal plantings. Irrigation is provided through underground sprinkler systems laid parallel to the main walkways. The department has also developed gardens between Vidhana Soudha and the High Court, featuring irrigation, shrubs, Mexican grass, and topiary works.[31]

During flower shows, floral replicas of Vidhana Soudha have been created. In the 2023 annual Independence Day flower show at Lalbagh, a replica measuring 18×36×18 ft was assembled using over 7.2 lakh flowers; in the Dasara flower show at Kuppanna Park (Mysore), a replica was made from more than one lakh roses. Installations on the Vidhana Soudha lawns have included 12 ft-tall peacock topiaries and a Gandabherunda replica made of fibre-reinforced plastic adorned with multiple flower types.[31]

Urban planning measures are taken to prevent tree roots from affecting the underground metro station beneath the premises.[31]

Proposed rooftop hanging garden

[edit]In 2008, the Karnataka Horticulture Department proposed converting the elevated parking deck of Vidhana Soudha into a rooftop hanging garden inspired by the Hanging Gardens of Babylon. The plan envisioned lawns, flowering plants, and aromatic native trees crowning the granite structure. Though preliminary clearances and site cleaning were initiated, the project remained unrealized due to logistical constraints.[34]

Significance and public interface

[edit]Permanent façade illumination

[edit]On 6 April 2025, Vidhana Soudha was outfitted with a permanent LED-based architectural lighting system, inaugurated by Chief Minister Siddaramaiah. Designed to highlight the grandeur of the granite facade, the lights are programmed to operate from 6:30 PM to 10 PM on weekends and public holidays, using color themes that reflect national and cultural occasions.[8][35]

Civic space and public gatherings

[edit]For much of its early history, the lawns and broad avenues around the Vidhana Soudha were accessible public spaces where citizens assembled for civic ceremonies, rallies, and protests. Demonstrators often gathered around the statue of Dr. B. R. Ambedkar, installed in 1981 on the building’s eastern front, using the symbolic presence of the Constitution’s architect to frame their causes.[36] However, following damage during protests in the 1990s and a High Court directive in 1997, the government banned mass gatherings in the immediate vicinity of the building. Since then, large protests have been redirected to Freedom Park, though symbolic sit-ins and smaller demonstrations still occasionally take place at the Ambedkar Veedhi.[37][38]

This shift in access reflects what historian Janaki Nair describes as a broader attempt to contain "plebeian democracy" through spatial restrictions and symbolic remapping. In her 2002 study, Nair highlights how Vidhana Soudha’s surroundings—particularly Cubbon Park—once functioned as vibrant grounds for democratic assembly, hosting protests like the Non-Gazetted Officers' (NGO) strike of 1965, the 1973 anti-price-rise protest (with over 100,000 participants), the Public Sector strike of 1981, Dalit Sangharsh Samiti (DSS) rallies, and farmers’ jathas.[39] Nair also critiques the architectural and ceremonial use of the building’s eastern façade—particularly the grand staircase—as enabling a form of "royal darshan," where citizens are positioned as spectators rather than participants. This performative use of space began in 1985, when Chief Minister Ramakrishna Hegde broke precedent by holding his swearing-in ceremony on the steps of Vidhana Soudha instead of inside Raj Bhavan, setting a template for future governments.[39]

The public space surrounding Vidhana Soudha has additionally served as a canvas for symbolic representation through statuary. In 1979, following sustained advocacy by Dalit organizations, Vidhana Veedhi was renamed Ambedkar Veedhi, and a statue of Dr. Ambedkar was installed in 1981.[39] This was followed by statues of Jawaharlal Nehru and Subhas Chandra Bose on the eastern lawns, while regional leaders like Kengal Hanumanthaiah and Devaraj Urs were commemorated on the western lawns, reinforcing a subtle distinction between national and state leadership.[39]

Despite restrictions, Vidhana Soudha remains a significant site for civic expression. In April 2025, Karnataka BJP leaders protested in front of the statue of Kengal Hanumanthaiah, opposing the suspension of 18 MLAs and theatrically tearing bill copies.[40] The building has also witnessed confrontations between legislators and police, cementing its status as a theatre of Karnataka’s democratic life.[40]

In February–March 2025, the Karnataka Legislature hosted its first public book fair on the premises, featuring 151 stalls (80% Kannada literature), poetry readings, and panel discussions. Chief Minister Siddaramaiah announced it would become annual, with MLAs permitted to use ₹2 lakh from Local Area Development funds to donate books.[41] In January 2023, foundation stones were laid for statues of Kempegowda and Basaveshwara, aiming to inspire a "New Karnataka."[42] A rare statue of Head Constable Marichikaiah Thimmaiah near Raj Bhavan Road symbolizes civic recognition beyond political figures.[43]

Notably, Vidhana Soudha hosted the 2nd SAARC Summit (16–17 November 1986), with the Legislative Assembly chamber serving as the venue for regional heads of state.[7][44]

These developments reflect Vidhana Soudha’s transformation into both a governance site and a civic landmark—retaining protest symbolism while embracing cultural programming and democratic engagement.

Impact of proposed urban development projects on the vicinity

[edit]Urban development plans around Vidhana Soudha, particularly the proposed 16.7-kilometre underground tunnel road project in Bengaluru (estimated at ₹17,780 crore), present complex governance challenges. Deputy Chief Minister D. K. Shivakumar instructed planners to ensure that no tunnel road exit ramps be located within a 1 km radius of Vidhana Soudha, in order to prevent traffic congestion in the high-security zone.[45] The draft Detailed Project Report (DPR) had initially proposed two exit ramps near the building, citing high traffic volumes at key junctions.

While aesthetic enhancements—such as the 2014 facade facelift and the 2025 LED lighting upgrade—have been carried out,[29] concerns remain about neglected core infrastructure. For example, reports have noted that security scanners at the complex were non-functional for extended periods.[29] This juxtaposition between visual beautification and lapses in security infrastructure points to possible gaps in administrative priorities.

Efforts such as the introduction of guided tours aim to improve public engagement and access,[29] yet the special precautions around the tunnel road project illustrate the symbolic and functional centrality of Vidhana Soudha in Karnataka’s governance landscape. These developments reflect the broader challenge of balancing rapid urban modernization with the preservation and functional dignity of historic civic landmarks.

Efforts such as the introduction of guided tours aim to improve public engagement and access,[29] yet the special precautions around the tunnel road project illustrate the symbolic and functional centrality of Vidhana Soudha in Karnataka’s governance landscape. These developments reflect the broader challenge of balancing rapid urban modernization with the preservation and functional dignity of historic civic landmarks.

Security incidents

[edit]As the seat of Karnataka’s legislature and a prominent symbol of government authority, Vidhana Soudha has been the site of several notable security incidents in recent years.

July 2023: Intruder with expired pass On 7 July 2023, during the presentation of the state budget, a 72-year-old man breached security by entering the building using an expired entry pass. The incident exposed critical flaws in access control protocols. In response, authorities launched a special drive to confiscate over 250 invalid passes and reinforce entry procedures at the legislature complex.[46][47]

January 2024: Self-immolation attempt In January 2024, a family of eight attempted self-immolation outside the main entrance to protest the auction of their home by a bank. Police intervened before injuries occurred. The incident underscored the challenges of managing spontaneous protests near the high-security complex.[48]

Public access and guided tours

[edit]Vidhana Soudha opened for public guided tours on 1 June 2025, a joint initiative by the Karnataka State Tourism Development Corporation (KSTDC), the Speaker's Office, and the Vidhana Soudha Security Division.[9] The tours aim to promote public engagement with the state's legislative heritage.

Logistics

[edit]- Schedule: Tours operate on all Sundays and the second/fourth Saturdays of each month from 8:00 AM to 5:00 PM, excluding days with legislative sessions or security restrictions.[49]

- Capacity: Groups of 30 visitors each, with 10 slots daily (300 visitors/day). Tours last 90 minutes and cover 1.5 km, including the Assembly Hall and foundation stone.[50]

- Tickets: ₹50 for adults; free for students under 16 (with school ID and Aadhaar). Foreign nationals must present passports.[51]

Booking and security

[edit]- Registration: Mandatory online booking via KSTDC's portal, with limited walk-in availability.[52]

- ID requirements: Physical Aadhaar, voter ID, or passport (digital copies not accepted).[53]

- Prohibited items: Plastics, food, drones, and non-water beverages. Entry is restricted to Gate 3.[54]

Educational focus

[edit]Officials describe the tours as a "democracy immersion" initiative. Speaker U.T. Khader stated the goal is to inspire civic responsibility,[50] while Law Minister H.K. Patil called Vidhana Soudha a "temple of democracy".[54] Guides explain the building's neo-Dravidian architecture, influenced by temples at Aihole and Pattadakal, and its construction under Chief Minister Kengal Hanumanthaiah.[55]

Historical context

[edit]The program follows similar public-access models at Rashtrapati Bhavan and the Parliament of India.[56] Veteran guide Gnana Shekhar (employed for 25+ years) provides historical narratives during tours.[55]

Similar buildings

[edit]

- The Government of Karnataka constructed a similar building named Vikasa Soudha to the south of Vidhana Soudha. Initiated by the then Chief Minister S. M. Krishna and inaugurated in February 2005, it was intended to be an annexe building, housing some of the ministries and legislative offices.[57][58]

- The Suvarna Vidhana Soudha (lit. 'Golden Legislative House') is a building in Belagavi in Northern Karnataka which was inaugurated on 11 October 2012 by then President Pranab Mukherjee. The building serves as an alternate to Vidhana Soudha and hosts the state legislature.[59]

- To decentralize administrative functions and bring government services closer to the people, the Karnataka government initiated the construction of "Mini Vidhana Soudhas" across various districts and taluks. These structures are designed to house multiple government departments, facilitating easier access for citizens. For instance, the Mini Vidhana Soudha in Mangaluru consolidates offices related to taluk administration under one roof, including the taluk office, the office of the Assistant Commissioner, sub-registrar offices, and land records departments.[60]

In 2018, the Karnataka government announced plans to construct 50 new Mini Vidhana Soudhas across the state, with land identified in various taluks for this purpose.[61] These buildings are modeled after the original Vidhana Soudha in Bengaluru, reflecting similar architectural elements and serving as symbols of governance at the local level.

However, there have been discussions about renaming these structures to better reflect their function. In 2021, Revenue Minister R. Ashoka mentioned that the Karnataka government would consider renaming Mini Vidhana Soudhas as "Taluk Adalitha Soudha" (Taluk Administrative Buildings) to more accurately represent their role in local administration.[62]

References

[edit]- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l Lingaiah, K. (1998). Vidhana Soudha: A Chronicle of Karnataka’s Legislative Landmark. Bengaluru: Karnataka State Gazetteer Department.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z aa ab ac ad ae af ag ah ai aj ak al am an ao ap aq ar as at Prakash, N. Jagannath (2001). Shilakavya: A Hand Book on Vidhana Soudha (in Kannada). Bangalore: Anthargange Prakashana. pp. 30–31.

- ^ a b c d e Lang, Jon T.; Desai, Madhavi; Desai, Miki (1997). Architecture and Independence: The Search for Identity – India 1880 to 1980. Delhi: Oxford University Press. p. 343. ISBN 978-0195639001.

- ^ a b Issar, T. P. (1994). Blossoms of Bangalore. Bangalore: Marketing Consultants & Agencies Ltd. p. 88.

- ^ a b Indian Philately.net – Karnataka Permanent Pictorial Cancellations

- ^ a b Press Information Bureau, 25 October 2017 – Address by President Kovind at the Diamond Jubilee of Vidhana Soudha

- ^ a b SAARC Secretariat – 2nd SAARC Summit Declaration

- ^ a b Hindustan Times, 7 April 2025 – Vidhana Soudha Gets New Lighting

- ^ a b "Vidhana Soudha in Bengaluru to be open for guided tours from June 1". The Hindu. 27 May 2025. Retrieved 29 May 2025.

- ^ "Mini Vidhana Soudha name to be changed: R Ashoka". Deccan Herald. 6 September 2021. Retrieved 31 May 2025.

- ^ a b Nair, Janaki (2011). Mysore Modern: Rethinking the Region under Princely Rule. University of Minnesota Press. pp. 284–286. ISBN 978-0816673841.

- ^ "Know Your City: How construction of Vidhana Soudha turned into a symbol of Karnataka pride". The Indian Express. 10 April 2023. Retrieved 29 May 2025.

- ^ Kapoor, P. C., ed. (1957). "'Government's Work Is God's Work'—Inscription To Go". Civic Affairs. Vol. 5. Citizen Press. p. 44.

- ^ Lang, Jon T.; Desai, Madhavi; Desai, Miki (1997). Architecture and Independence: The Search for Identity – India 1880 to 1980. Delhi: Oxford University Press. p. 204. ISBN 978-0195639001.

- ^ Ranganna, T. S. (29 August 2012). "A wall at Vidhana Soudha demolished". The Hindu. Archived from the original on 6 December 2019. Retrieved 15 February 2015.

- ^ "Neglected Mallasandra quarry a haven for criminals". The New Indian Express. 2 November 2021. Retrieved 29 May 2025.

- ^ "Govt plans facelift for Vidhana Soudha". Deccan Herald. 1 August 2014. Retrieved 30 May 2025.

- ^ "Vidhana Soudha decked up in LED lighting". The New Indian Express. 7 April 2025. Retrieved 30 May 2025.

- ^ "Karnataka: Bengaluru's Vidhana Soudha gets permanent lighting". Hindustan Times. 7 April 2025. Retrieved 30 May 2025.

- ^ "Vidhana Soudha not a heritage building yet: HC". Deccan Herald. 11 June 2013. Retrieved 30 May 2025.

- ^ Bengaluru Prayana – Permanent Pictorial Cancellations in Karnataka

- ^ CollectorBazar – 1962 Commemorative Cover featuring Vidhana Soudha

- ^ Stamp Digest – Special Covers India 2025: Suvarna Vidhana Soudha

- ^ Ramkissoon, Reuben A. (2006). Gandhi: A Philatelic Handbook on Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi. R&W Enterprises.

- ^ "There is a liftman in all of us". The New Indian Express. 16 March 2017. Retrieved 30 May 2025.

- ^ "Lift Man Movie Review". The Times of India. 12 May 2017. Retrieved 30 May 2025.

- ^ "Photo movie review: A powerful indictment of lockdown mismanagement". Deccan Herald. 14 March 2024. Retrieved 30 May 2025.

- ^ "Photo review: A mirror to the realities of the lockdown". The Times of India. 14 March 2024. Retrieved 30 May 2025.

- ^ a b c d e f "The Sunday Read: Tale of Two Buildings". Bangalore Mirror. 11 March 2024. Retrieved 30 May 2025.

- ^ Lang, Jon T. A Concise History of Modern Architecture in India. Orient Blackswan, 2002, pp. 40–41.

- ^ a b c d e "Vidhana Soudha: The Landscaping Vision". Mysore Information Bulletin. Government of Mysore. March 1954.

- ^ Times of India, 24 March 2015 – Tabebuia blooms around Vidhana Soudha

- ^ Times of India, 4 March 2019 – Bengaluru in Bloom

- ^ Bangalore Mirror, 22 August 2008 – Hanging Gardens at Vidhana Soudha

- ^ New Indian Express, 7 April 2025 – LED Lighting at Vidhana Soudha

- ^ Shetty, O. (2020). The Lost Commons of Bengaluru, Medium.com – [1]

- ^ Bangalore Mirror, 28 January 2022 – Flash Protest at Vidhana Soudha

- ^ Times of India, 3 October 2023 – Protesters Stopped on Ambedkar Veedhi

- ^ a b c d Nair, Janaki. "Past Perfect: Architecture and Public Life in Bangalore." The Journal of Asian Studies, vol. 61, no. 4, Nov. 2002, pp. 1205–1236.

- ^ a b "The News Minute, 2 April 2025 – BJP Protest at Vidhana Soudha". Archived from the original on 31 May 2025. Retrieved 31 May 2025.

- ^ ETV Bharat – Karnataka Book Fair at Vidhana Soudha

- ^ The News Minute, 13 January 2023 – Foundation Stones for Statues

- ^ Mint Lounge – A Statue for a Head Constable

- ^ Times of India, 2 October 2017 – Vidhana Soudha at 61

- ^ "Tunnel road in Bengaluru: Karnataka Dy CM asks planners not to have exit ramps within 1 km of Vidhana Soudha". The Indian Express. 29 May 2024. Retrieved 30 May 2025.

- ^ "Vidhana Soudha security team seizes 250 fake passes". Deccan Herald. 8 July 2023. Retrieved 30 May 2025.

- ^ "Police seize counterfeit, expired passes at Vidhana Soudha". Hindustan Times. 8 July 2023. Retrieved 30 May 2025.

- ^ "Family tries to self-immolate outside Vidhana Soudha". Hindustan Times. 10 January 2024. Retrieved 30 May 2025.

- ^ "What to expect from Vidhana Soudha guided tour". Deccan Herald. 25 May 2025. Retrieved 29 May 2025.

- ^ a b "Vidhana Soudha opens doors to public for guided tours from June 1". The New Indian Express. 26 May 2025. Retrieved 29 May 2025.

- ^ "Activities". Karnataka State Tourism Development Corporation. Retrieved 29 May 2025.

- ^ "Now, you can take a guided tour of Vidhana Soudha in Bengaluru". The Hindu. 9 April 2025. Retrieved 29 May 2025.

- ^ "You Can Now Take A Guided Tour Of Bengaluru's Vidhana Soudha". The Unstumbled. Retrieved 29 May 2025.

- ^ a b "Vidhana Soudha guided tours to begin June 1". Daijiworld. 25 May 2025. Retrieved 29 May 2025.

- ^ a b "Bangalore's Vidhana Soudha: The Pride of Karnataka". Metro Times. Retrieved 29 May 2025.

- ^ "Bengaluru's Vidhana Soudha to open for public tours on holidays". Hindustan Times. 25 May 2025. Retrieved 29 May 2025.

- ^ "13-yr-old Vikasa Soudha gets into 'heritage list'". Bangalore Mirror. 30 November 2017. Archived from the original on 4 February 2022. Retrieved 4 February 2022.

- ^ "15 years on, netas still see Vikasa as the lesser Soudha, insist on Vidhana office". The New Indian Express. Archived from the original on 4 February 2022. Retrieved 4 February 2022.

- ^ "A new chapter begins today". The Hindu. 11 October 2012. Retrieved 1 December 2023.

- ^ "Mangaluru's Mini Vidhana Soudha finally inaugurated". Coastal Digest. Retrieved 29 May 2025.

- ^ "Mini Vidhana Soudha to be built on govt land". Bangalore Mirror. Retrieved 29 May 2025.

- ^ "Mini Vidhana Soudha name to be changed: R Ashoka". Deccan Herald. Retrieved 29 May 2025.

Further reading

[edit]- Prakash, N. Jagannath. Shilakavya: A Hand Book on Vidhana Soudha. Bangalore: Anthargange Prakashana, 2001. ISBN 9788178240176.

- Lang, Jon T. A Concise History of Modern Architecture in India. Hyderabad: Orient Blackswan, 2002. ISBN 978-81-7824-017-6.

- Scriver, Peter, and Srivastava, Amit. India: Modern Architectures in History. London: Reaktion Books, 2015. ISBN 978-1-78023-523-2.

- Chalana, Manish, and Krishna, Ashima (eds.). Heritage Conservation in Postcolonial India: Approaches and Challenges. New York: Routledge, 2020. ISBN 978-0-367-62430-9.

- Prakash, Vikramaditya. One Continuous Line: Art, Architecture and Urbanism of Aditya Prakash. Ahmedabad: Mapin Publishing, 2020. ISBN 978-81-89995-68-3.

Français

Français Italiano

Italiano